Delegation and the NASW Code of Ethics

The issue of delegation of authority is an important concept for board members, staff, and relevant attorneys to understand. In short, the legislature enacts statutes that create and delegate authority to the social work boards to enforce the practice act in the interest of public protection. Where appropriate, social work boards delegate authority through the promulgation of rules/regulations that recognize programs as a means of increasing efficiencies, providing fiscal management, and promoting uniformity.

The ASWB examination program is such an example. Use of the exams to assess applicants’ entry-level competence increases regulatory boards’ efficiencies and effectiveness. In addition, a defensible examination program promotes uniformity across jurisdictions. Another justification for regulatory board delegation regarding the examination program is the composition of ASWB. Uniquely, ASWB is a not-for-profit membership organization whose members are composed of government social work boards. Member boards’ use and reliance upon programs offered by ASWB—in effect, member boards’ “own” programs—separate ASWB from other organizations, such as professional/trade organizations.

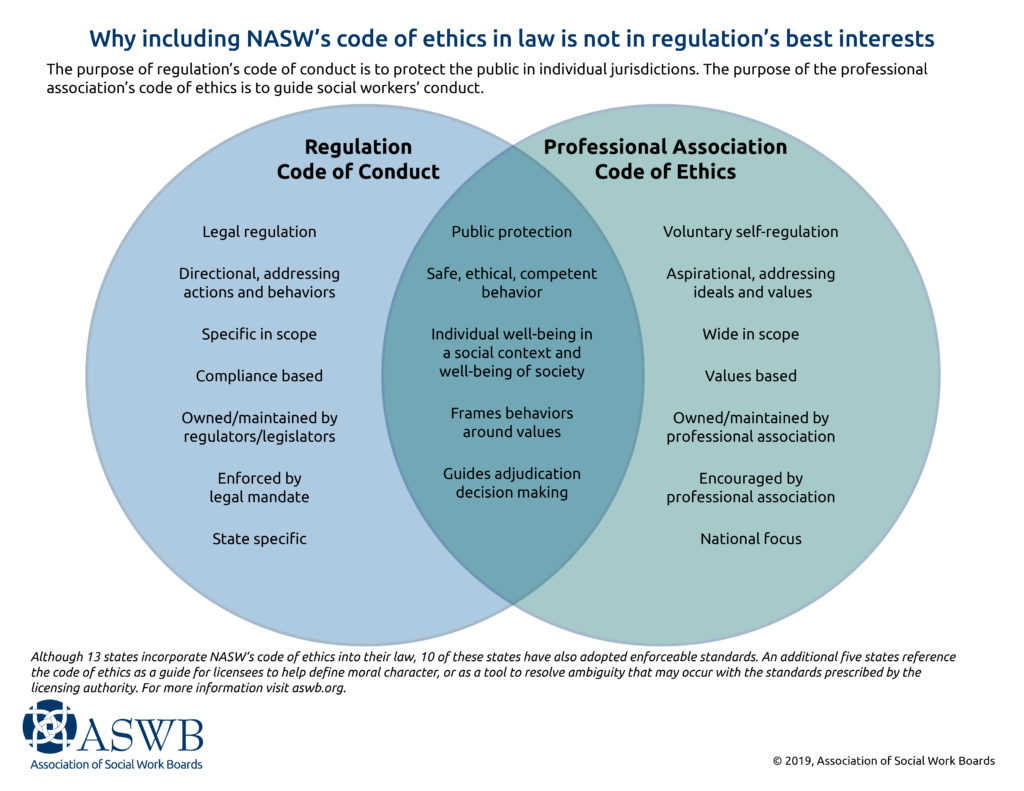

A number of ASWB member boards have asked about incorporating the code of ethics of the National Association of Social Workers, a professional/trade association, into rules/regulations by reference. Specifically, to incorporate “by reference” means to name the NASW Code of Ethics within the statutes and/or rules/regulations as the standard to which licensees will be held accountable. That is, a licensee’s failure to comply with these standards may result in an adverse action against the government-issued license.

According to its website, NASW “is a membership organization that works to enhance the professional growth and development of our members, to create and maintain professional standards for social workers, and to advance sound social policies.” NASW members are individual social workers. Referring in law to the NASW Code of Ethics is a form of delegation by government to an outside private entity, namely a professional/trade association.

As distinguished from delegation of authority to ASWB, delegation of authority to the professional/trade association is fraught with legal issues and creates an optic of self-regulation and the potential for self-serving, protectionist regulation. For legal and practical reasons, ASWB has always taken the position that the jurisdiction should enact statutes and/or promulgate regulations using the language determined necessary to adequately regulate the profession in the interest of public protection, rather than simply naming the NASW code.

Indeed, Article II, Section 213 of the ASWB Model Social Work Practice Act employs language that legislatively delegates authority to the social work board, a governmental entity, to use its expertise in determining the appropriate education, examination, and continuing education providers/programs for licensure eligibility and renewal.

ASWB consistently stands for the proposition that legislatures statutorily authorize the boards, which in turn promulgate rules/regulations that place into law language necessary to effectively and efficiently enforce the legislative intent. This process ensures that the board, as a governmental entity—rather than a private-sector organization—ultimately determines required licensure criteria. As a result, mandatory criteria are determined by government, not by the private sector.

When addressing potential adverse action(s) against a government-issued license, the respondents are entitled to due process of law. Due process, a fairness principle, requires that licensees be able to understand what law, rule, or regulation they have been accused of violating. Vague or subjective requirements may not form the basis for enforcement of a government-issued license. If licensees are accused of violating a code that contains aspirational language rather than definitive language, they may be incapable of understanding these requirements.

Failure of government to enact laws (statutes and/or rules/regulations) that are capable of being understood by the common licensee may result in unenforceable criteria. Respondents will argue that attempting to enforce a code that is unable to be understood violates their due process rights.

Ethical principle: Social workers respect the inherent dignity and worth of the person. Social workers treat each person in a caring and respectful fashion, mindful of individual differences and cultural and ethnic diversity. Social workers promote clients’ socially responsible self-determination. Social workers seek to enhance clients’ capacity and opportunity to change and to address their own needs. Social workers are cognizant of their dual responsibility to clients and to the broader society. They seek to resolve conflicts between clients’ interests and the broader society’s interests in a socially responsible manner consistent with the values, ethical principles, and ethical standards of the profession.

Under due process principles, government would be hard-pressed to sanction a licensee under alleged violations citing the above. Vague and subjective terms and concepts threaten the due process requirements owed to a licensee. Numerous additional examples exist in the current NASW code.

To the extent that an ASWB member board wishes to take advantage of already existing codes of ethics and standards of practice, it is suggested that the board(s) promulgate the specific language into the rules/regulations. Prior to promulgation, boards should seek and follow advice from their respective counsel, who will consider the due process and other legal considerations necessary to ensure enforceability of the rules/regulations.

Counsel’s column